This article contains themes and discussion of sexual assault.

You are thirteen years old, walking towards the creek at the end of your street.

Small pieces of rubble from the middle of the road come loose and disperse under the tires of a passing car. The metal rims scintillate under the last afternoon light.

The grass bubbles from the pulse of the creek bed. You take your shoes off. The crickets are singing, the stream rumbles softly, the wet ground vibrates with the hum and bustle of insects between your toes.

In the reflections of the ripples, browns and mossy greens blur like paint stripes. A reddish leaf is pulled along by a string of currents. The leaf floats across the reflection of your cheeks, the current dragging the edges of your face.

The ripples flash a warm yellow as the street lights flicker on behind you. Time to go home.

Later you would come to realise that this was the last time you visited the bank of that creek, and as a result, that curious, innocent version of you would be imprisoned behind those tides irredeemably.

We all have a version of that creek – a hidden ghost of our former selves, entrapped within the blissful ignorance of a time prior to knowing what we know now. Dilara Findikoglu’s SS26 Runway, Cage of Innocence, is an exploration of the treacherous plight back to that place.

Emerging from a conservative upbringing, Findikoglu has

pioneered her fashion house as a tool to deconstruct patriarchal confines, as much as a gothic dreamworld filled with visions of escapism and symbols of the occult.

Born in Istanbul, Findikoglu moved to London at the age of nineteen to study fashion design at Central Saint Martins. Her looks became associated with outcasted crowds after she staged an unauthorised ‘guerilla’ collection to showcase her graduate thesis as well as other student collections who didn’t make the official press show. Even as Findikoglu transitioned into a mainstream designer, her fearless handling of ‘otherness’ has become a signature trait of her work:

“In Islam, they tell you about an unknown world, the world of spirits – they’re called jinn in Arabic – and these creatures that live in other dimensions. I was scared of this world but, at the same time, felt close to it. I used to wish I was psychic so I could discover more about it.”

(Another Man)

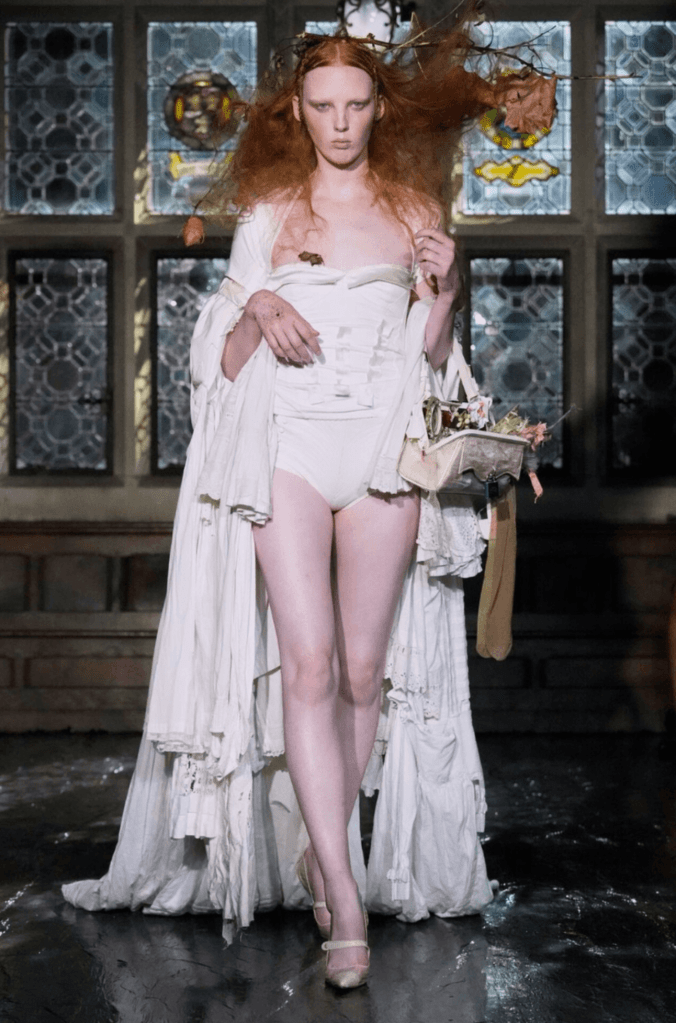

Each look in Findikoglu’s runway is a disquisition on how innocence moves with us as we emerge as women. In the beginning of the show, models appear shaky and disheveled, with mud smeared up their legs and branches entangled in their wild, teased hair.

Unkemptness and disarray transition into something much more structured as the show progresses, with hair falling smooth and tightly braided, and flowy ripped fabrics transitioning into stiff boned leather. ‘Cages’ appear in metaphorical forms – chainmail ornaments are applied directly to the face as an armour shielding the eyes and cheeks. Necklines reach high to choke its models. Latex gloves and tubed silhouettes tighten and constrict the form.

In one look, Findikoglu gives her model a horsebit buckle headpiece. This look in particular achieves a certain ‘shock value’ – the ‘cage’ becomes so literal here it almost mimics some kind of torture device. As confronting as it is designed to be, Findikoglu never allows us to fall out of the underlying narrative, each garment flowing into the next as designs pulsate between constriction and release.

It’s hard to express the specific and complex relationship women have with innocence, yet Findikoglu’s looks imitate it well. For young girls, childlike innocence is extremely precarious. In Australia it is estimated that females are twice as likely to have experienced child sexual abuse than males. That’s more than 1 in 3 girls who are robbed of their childhoods – the most liberating, untainted time of their lives. Those who do not fall victim to CSA are not exempt from falling victim to other predatory behaviours delivered predominately at the hands of men, throughout the rest of their lives. Think of every time you’ve been catcalled, stared at, followed, sent unwanted explicit messages. Would it be too provocative of me to assume that inside every women is a fundamental belief that she is unsafe in this world?

The hand that so unjustly takes innocence away from young girls, is often the same that places unrealistic expectations of purity upon adult women. The concept of ‘purity’ is so deeply engrained in the metrics of what is deemed ‘attractive’, or even ‘acceptable’ within society, a ticket to extend your desirability long past your use-by date of 30. How many men’s skincare brands can you think of that make products to reduce the appearance of wrinkles by 20 years? ‘Skinny’ is back, but only for women. Is the recent Ozempic Pandemic a pursuit of appearing young and waiflike rather than managing health? Why is it that the idea of men’s body hair is innocuous, yet having a bush is a ‘political statement’?

Findikoglu’s collection explores the effect that the control of female innocence has on women’s relationships with themselves, and with each other. On the runway, she presents the idea of ‘innocence’ and the idea of the ‘cage’ within the same equal plane. The looks speak to each other – for example, the cherries used to stain a corseted ivory tube dress are echoed in another look where cherries and feathers spill out of a handbag. In the latter look, the model also wears a corseted dress, however this one appears tightly tied at her shoulders. Her hair is braided like a rope, her eyes are wide and mud is smeared across her forehead giving her a ‘hunted’ appearance. In a third monochromatic red look, the girl is ‘contained’- her extremities are bound in latex gloves and socks, her arms are cuffed to the elbows with metal bangles, and her dress conceals her body from her neck to her ankles, with metal stitching running down between the legs.

The communication between her designs was not unintentional – in an interview with 032C Magazine, Findikoglu shares her deliberate use of red in her clothes:

“I love the colour red because, when I was graduating, I had the sense that red was my personality. It has so many tones, and it is so difficult to get the right one. And it can mean so many things. It can mean love, passion, fearlessness. It is so bold, so out there. If you’re wearing red, it’s difficult to hide. I just want it to be heard and seen. It’s not a mid-tone. It’s red. It’s not black, and it is not white. It’s also the colour of blood—it’s quite crazy. When it’s

diluted it becomes pink and cute.”

Findikoglu marries red tones despite their contrasting playful and restrictive contexts. By changing the opacity of colour within a look – be it diluted cherry stains or head to toe striking red -Findikoglu builds a sense of power and reclamation. She wants both voices – the hunted girl with sticks in her hair and cherry juice across her legs, and the caged woman with a sleek silhouette and smooth straight hair, to be equally seen. In fact, both women are one and the same, just expressed differently. Findikoglu illustrates that our child self is always living inside of us- their red passion, and fearless thirst for life remains internally unbounded despite how constricted by social pressures we may

become.

In this runway, Findikoglu takes us back to that creek bed at the end of the street. We can feel the textures of wild nature, yet perceive it through an older, more contained lens. It’s like looking at innocence from the other side of time, from within the cage. Yet, it is in the way the garments accentuate the female form, the way that the models gaze with steadfast assurance, the walks that transition from shaky to strong, that indicates to me a certain power in femininity. Perhaps a knowledge that our innocence is sacred, and the fierceness we possessed as girls is our compass into womanhood.

Words by Lola Haylock. @the.divine.archive