Without giving too much away (like my personal address) it is with great neutrality that I confess that my suburb is finally getting a makeover, and that my childhood home is most likely going to double in value within the next 5 years.

There’s no denying the steady, almost bubonic sprawl inching further west with each passing year, as more and more funding goes into gentrifying our western suburbs to accommodate a growing population.

At university, I quickly learned that most of my friends had no real idea where I lived—geographically or otherwise. Anything beyond the northern side of the bridge might as well have been regional.

Maybe it was the internalised insecurity of growing up in a no-name suburb. Maybe it was the stigma of living somewhere that felt cryogenically frozen in 2002. Or maybe it was simpler than that. Maybe it was all my friends’ proximity to the coast, and my forty-five minute commute to a body of water, that really solidified our socioeconomic status on opposite sides of the spectrum.

But it’s 2026 now, and the living crisis in Sydney is at an all-time high. This means, for the first time in history, my suburb has been declared desirable by enigmatic TikTok real estate agents.

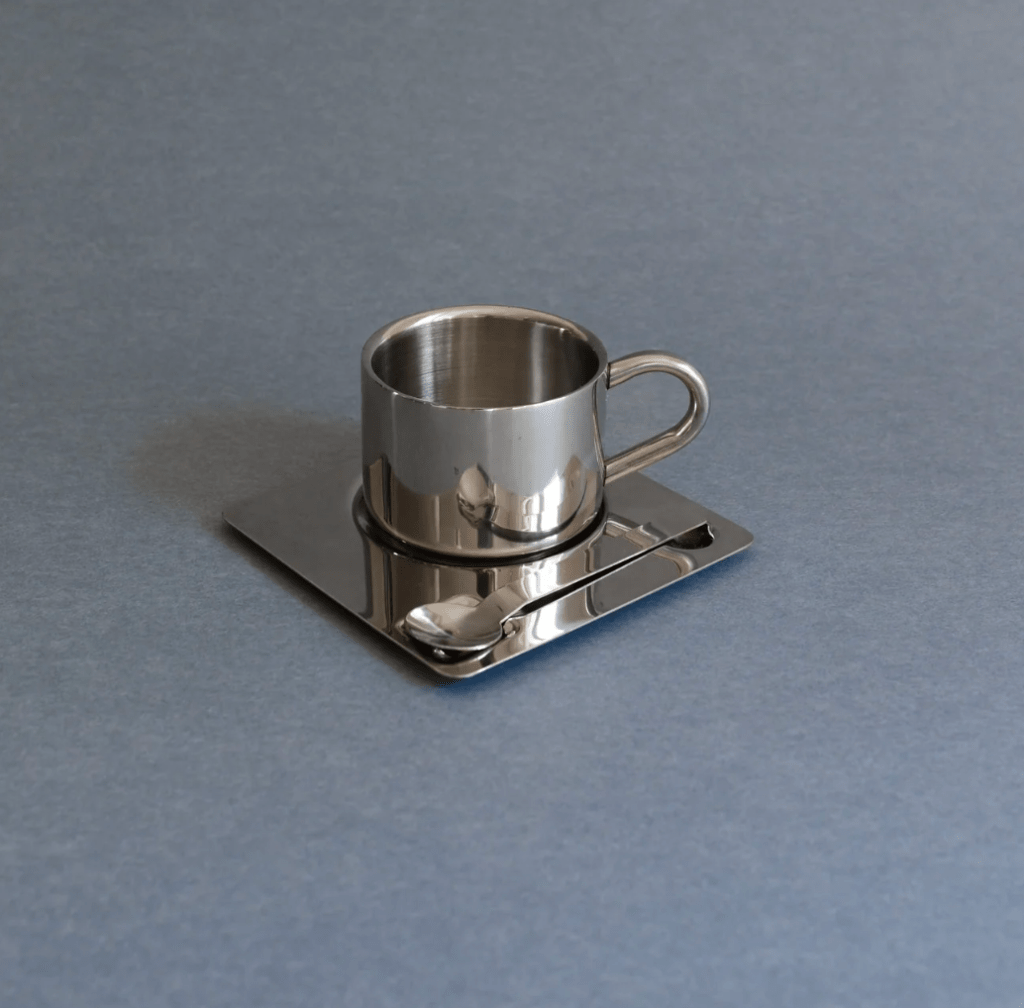

At a new coffee spot just minutes away from me—a converted warehouse, naturally— I sipped from my $10 cold brew, perusing the cafe’s Google reviews until the critique of a local foodie piqued my attention.

{Redacted} is the beginning of the end for this suburb: a sign that the creep of gentrification has truly reached its door.

Try living next door to two high-rise apartment blocks, I thought.

I kept scanning the familiar letters of my suburb’s name, in disbelief that anything remotely trendy could be synonymous with it.

For as long as I can remember, the main promenade of my suburb could be compared to the likes of a vibrant international strip––growers and sellers spilling onto the road, crates stacked too high, fruit sweating in the sun. It was too unorganised to feel metropolitan, yet the war memorial standing proudly in the centre was enough to snap you out of the hallucination.

Fragments of my suburb brought great comfort to me—a Cash Converters, permanently wrapped in “Closing Down” banners that had gone all sun-bleached and torn at the ends. Butchers that shouted in foreign tongues: cash only. Produce bartered by little ladies perched on milk crates, who boomed incoherent specials into a karaoke mic. The token charcoal chicken shop we frequented for a Friday night treat. And other fronts. I’m sure.

I didn’t spend much time there, it was slightly out of the way from my side of town, but I often passed through on the way home.

To me, it was iconic: bursting with no-frills culture and fast-paced calamity. It wasn’t my culture, exactly (you’d usually find me at the European deli in the adjacent suburb), but sometimes I wish I embraced it more, growing up.

For years, my friends and I caught up for coffee in the next suburb—fifteen minutes by bus felt like a necessary pilgrimage. I used to mourn the absence of a local café within walking distance from my house. Not just any café, but the kind tucked into the dormant remains of an old milk bar, or carved into a heritage building—you know the ones that line the streets of Surry Hills.

Now we have Swiss-water decaf on our doorstep and pilates studios, multiplying at an alarming rate. It feels strange to realise things aren’t just changing here, but they already have.

Recently, I immersed myself into the world of alternative medicine (because you either train for Hyrox in your late twenties or you start healing your gut). In the process, I discovered my suburb was riddled with Chinese herbalists, reflexologists and spiritual readers—services I had once travelled interstate to access.

What the hell?

With a smile, I tucked my medicinal herbs into my bag, waved at the jolly elderly couple, and walked home—peering into sage-infused studios, housing palm readers and other spots I’d saved on Google Maps along the way. Until recently, I would never have guessed I’d be wandering through my own suburb like a tourist.

Upon reaching my street, I took in the emptied blocks of land, standing awkwardly beside five-storey apartment buildings, the drilling humming like white noise at the back of my mind. A young-ish woman in Doc Martens and purple hair slipped into the brand-new complex, a family trailing behind her with their two golden somethings. I took notice of the mass immigration of purebred oodles cashing up around town.

But in all honesty, it is nice to see new faces, from all generations and demographics. There’s a strange comfort in being surrounded by families and younger couples choosing to build a new life here. Choosing my childhood suburb to call home.

Despite the passage of time and everything that comes with it, the bustling, unassuming version of the town I grew up in is forever etched into my memory.

And for now, I can’t deny the small indulgence of a $10 cold brew within walking distance.

Is that so terrible to admit?

Words by Yianna Tromboukis